Education is just a ride, so enjoy your journey and don't crush in the roadside trees. Reflections

15 Aug 2020

Disclaimer: some parts of the story may be upsetting or even, I hope, a bit scary 🎃. But all of it is an integral part of our human drama 🎭. Enjoy!

Last updated: 03.10.2020

Few pre-introductory words

I feel I have talked about myself too much. Therefore, I think this will be one of my last autobiographical pieces for a little while. I will try to focus attention on some other topics. But, after this journey, I feel I have done it, I had cast away most of my inner tensions. I finally think internally at ease 🧘. Everyone has a different outlet for dealing with life's challenges; for me, writing had become a tool of choice. I hope it only improves along the way.

Introduction

When I was between eight or ten years old I found an old book. It had yellow crumbling pages filled with a collection of short horror stories. Although all the details have faded in my head over the years, I still keep bumping into one tale's lingering echo inside the maze of my thoughts. My memory has always been selective, so naturally, I am making an unforgivable sin by forgetting the author's name. Yet, he or she did an amazing job because the core wit survived with me for so long. I will attempt to replicate it with a version of mine and save it in written form before it vanishes forever. The story goes something like this:

A young boy walks up to an old stone bridge. A thicket with long stretching branches and untidy bushy growths wrapped itself around the mouth of the entrance at each side of the bridge. Thick, dark and densely growing leaves blocked most of the sunlight. A trapped mist of coolness below the wild vegetation, rarely changed, even during hottest rural days. Water-loving mosses grew freely on the stone parapets of the bridge and felt wonderfully cool and smooth in touch, almost like melting icicles. The shade and coolness attracted many local kids who loved to splash in the river below during scorching summer days, while some hid there to escape farming chores.

The boy begins crossing over. From the opposite side, an adult man enters the bridge. The man smiles at the youngster, and the boy reciprocates with a radiant and proud grin full of youthful innocence. The man walks past the boy. A sudden chilling shriek from the thick overgrows breaks the peaceful moment. A monstrosity crawls out from the bushes, and then the man's face turns ghostly pale. The beast first stretches its four ugly legs and appears to have just woken from its slumber. With initial clumsiness but eerie swiftness, the creepy being fixates on the kid and begins making its way towards him.

The man doesn't hesitate; he turns around and grabs the boy and holds him in his arms for a brief moment. Without giving it too much thought, he tosses the youngster over the parapet of the bridge. The boy splashes into the river below. Paralysed by the sudden turn of events, he floats on the water like a plank of wood. The river's current swiftly pulls him under the bridge. When he re-emerges on the other side, he can see the man on the bridge tackling some horrible beast that resembled a crossover of a monstrous bear covered with bulging boils and appendages that resembled legs of a cockroach. But he had never seen anything as ugly as this abnormality. Then he loses consciousness, perhaps from the shock of the experience.

Years pass by. Samuel, the boy's name, forgets the encounter or perhaps dismisses it as a figment of his vivid childhood imagination, or a false memory that formed during countless plays with other kids. He remembers playing with other boys, and a couple of local girls to be a group of fearless warriors who fought an army of ungodly monsters. He grows up and moves to a nearby city for work. More years go by. As a mature man, Samuel returns to his childhood village to visit his family.

On Sunday afternoon he goes for a walk to the nearby forest in an attempt to recall his childhood memories. As he strolls further into the wild, he comes across an old stone bridge that rarely has any visitors as more families migrated to larger cities. His memory is hazy at this point, and he can vaguely recall that the bridge had ever been there. He begins to make his way across. He sees a young boy approaching from the opposite side. The boy is carrying a long stick and waves it like a sword. Samuel smiles at him, recalling the moments when he pretended to play as a fearless champion. The boy smiles back, but he quickly escapes the reality back into the domain of his childhood imagination. The boy waves his stick making whooshing sounds, occasionally he thrusts it forward, piercing and slashing the misty air. Samuel takes another step, but then his body freezes in place.

A morbid flash of terror runs through Samuel's body, like an electric shock, it makes him unable to move his tensed-up muscles. All of the traumatic memories suddenly return to him. He gets short of breath, and for a bit, the world starts spinning around him. He stumbles. He reaches with his hand the parapet of the bridge for some support. A few seconds later, a low growl and aggressive rustling in the bushy overgrowths break Samuel's focus on the rewinding the memories in his mind. He doesn't waste much time; he turns around and runs towards the boy; he knows what is about to happen.

A dense, almost chocking, putrid smell fills the air. A moment later, a disgusting beast crawls out from the nearby shrubs. But childhood memory dictates Samuel what to do. He tosses the boy into the stream below. The beast appears to understand that the man foiled its ambush. It growls with anger, and it grows in size as the hair on its back raise. Then it jumps against Samuel and with lightning swiftness it buries its claws deep into the man's belly tearing it open. Samuel gives out a long grunt. He uses his body weight to try to overpower and slow down the monstrosity, but he stumbles and can now feel warm blood flowing down his legs. When Samuel looks down his legs, he sees his intestines hanging out of his belly. They remind him of decorative strips of reddish-brown crepe paper which he used for decoration as a boy during his birthday parties. For a moment, the man smiles, but then his eyes fill with tears because he knows that the fight is almost over.

Samuel gathers his last strength. First, he punches the creature in the face, and then he tries to gauge its eye with his thumb. The beast is relentless, and it bites out man's fingers; they snap out of man's hand with ease. Then Samuel notes with the corner of his eye that the boy is now at a safe distance, floating on the surface of the river that runs into a small fishing lake. There should be some farmers nearby, and he hopes they would take care of the boy. With that brief thought, he exhales and drops on the ground.

You can probably wonder how I slept when I was a kid after reading chilling tales like that. I was terrified to close my eyes. Every tiny rustle or creaking in my countryside house made my heart almost pop out of my chest, sending waves of cold sweats on my back, and clot blood with adrenaline. But I loved these little thrills. I often sneaked out at night with some hope to spot wild spirits or beasts in abandoned houses, spooky forests or cemeteries. Alas, I never got lucky to see anything beyond the norm. Still, I got scared like hell by an occasional growl of a hedgehog browsing for insects in the nearby fields sown with barley.

I don't know precisely how we find our interests, but one section in the library provided me with books on medieval times and bits on the history of human mistreatment. From these books, I learned about the ugly side of human nature. It appears to me that we usually attribute our horrendous human acts to some spiritual beings or 'isms,' but I never accepted that. We never do things in the name of abstractions, but instead, we come up with these mental constructs to justify the times when our biologically wired impulses take over. The thought of that scared me more than any horror story because any human being can turn into an ugly beast that could rip open our flesh.

Anyway, I recall this short story for a different reason. When I was young, I had a hazy direction about my adult profession. I wanted either to become a pilot, a scientist, an engineer or an artist. The first profession was out of the question. I am coming from a farming family and to become an aircrew member was a privilege of a completely different social stratum. The idea of me pursuing a scientific path was quenched by a chemistry teacher that called me an idiot 🤪 in front of the whole class. I didn't see eye to eye with my biology and physics teachers too. When I moved between countries and found my way back into education, I resurrected that dream.

Pursuing a PhD in physics at the University of Bath a few years ago brought me closer to my childhood dream. Unfortunately, that dream quickly turned sour. I am finally ready to write more about it here. I realised I can still be an artist, but I doubt that I can pay the rent doing that yet, so I am trying software engineering to survive, for now.

In this perhaps bizarre way, I would like to warn you about that lurking beast you might have to face in your adulthood. But I urge you to fight it, so we can spare the young who can make it into the future. The beast I am thinking about is our primal human arrogance. Now when I think about it, ignorance and arrogance can both be served on the same plate, so I guess the beast can be an ugly hybrid of these two traits.

When I read Stephen King's autobiography [1] this year (2020), I admired him for being so candid about his life's experiences that fuelled his career. His scary stories brought so much joy into my life because I discovered that reading, combined with our aptitude to imagine, can set off many emotional cogs spinning inside our heads. Books to me are these great capsules packed with sentences evoking terrors, smiles, while some others make our eyes tear, or set us into wild adventures without stepping foot from our bedroom. I find Mr King's storytelling to be spectacularly digestible. His writing skill is universally understood and projects every tiny detail in one's head that can linger for days, or even years (at least in my case). I simply love the experience of reading his work.

When I am too lazy to create stories in my mind, I often admire watching movies. One of my favourite computer-animated movies is 'Ratatouille.' "Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere," is a quote that has been inspiring me for years (probably the additional element comes from the fact that I used to work in catering and enjoy good food). But I like twisting words and concepts. To make the quote more fitting to this post, I have to morph it. The result is the following: "not everyone is arrogant, but great arrogance can come from anywhere," - I include people in the system delivering and receiving an education; I am not immune to it either.

What is education and why I think we need it?

When we are kids, our prefrontal cortex is underdeveloped. Most of us don't have a strong sense to plan our future, and many of us, therefore, don't take adulthood too seriously (we procrastinate to deal with it later). As adults, on the other hand, we think that we can mould young people into adults by applying educational schemas that we experienced. But this approach is just wrong. We go through several 'stages' of development, which are rarely linear and occur at different speeds that vary between individuals. The inter-human interactions are chaotic, and the same conditions that we set out for life can bring about different results for others.

In the past, we developed cookiecutter systems to force the knowledge through dreaded suppositories that were never pleasant and made us clench our butt cheeks for hours in order not to make a horrid mess from our guts. Thankfully to the efforts of some remarkable educators and psychologists, who through dynamic research and adaptation in the past several decades, made it less unpleasant. Furthermore, many volunteers are producing complimentary and more digestible online resources that we can utilise to patch the gaps of knowledge we missed to understand at school.

Unfortunately, some of us experience a sudden shock when we enter the 'adulthood' sober; at least that's what I first felt deep through my marrow. "Oh, I wish I prepared myself better for this disaster," I kept telling myself scrubbing a pile of dirty dishes ten or twelve hours a day on foreign territory. I thought I messed up.

I didn't have to hear another sermon that education is vital after I crawled into bed after day's work. After a seven-day working week, I lost connection with my body, inside my mind, I just flipped a switch to an autopilot mode. I acted akin to 'Boxer' in Orwellian novella 'Animal Farm,' by reciting a mantra: 'I will work harder,' to keep the momentum. Sadly, I didn't read it at the time. So I suggest that you pick up the book and stop acting like 'The Foolish Old Man' from a Chinese fable [2]. This way, you might stop and think before you commit yourself to hard labour.

Reading is an excellent way to acquire wisdom informally. I was lucky to have early access to books. When I was old enough, I walked alone to my nearest library, which was just a few kilometres away from my home. Unfortunately, I can't say the same about reading my school's textbooks; they were as rough as the toilet paper made during the communist days*.

* Probably you can notice throughout my writings that I heavily dislike isms, some more and some less, but communism irritated me intensely. It was a system that built on so many layers of axiomatic crap I can't comprehend that anyone could take it seriously. Perhaps it makes sense why seriousness became currency to the people living under the system, or why the system had to force its critics into hard labour. Yet today, one can praise communism for its ability to produce so many millionaires, and even billionaires, in the name of equality.

I picked up reading due to curiosity. I think when I was six, I attempted reading a book on 'General Pathology', although it was in my native language*. From the text, I have begun learning about inner parts of the body, their interactions and what roles they play to drive us around. At the time, I didn't understand most of it, but I kept trying until I learned the defining words throughout the years. Human knowledge fascinated me.

* This explains why my written English may still sound unnatural; you can forgive me though because I promise to continue working hard of making it more understandable by slowly incorporating Gwynne's grammar [3]

The force that pushed me to read and learn was powerful, I often walked these terrifying kilometres to reach the library - for tiny legs, this was a mighty adventure. Being small and vulnerable had some disadvantages - walking long distances meant I had a chance to stumble upon dogs, pigs or geese that roamed the neighbourhoods. Most of the time, I armed myself with some kind of heavy stick and few pebbles stocked inside my pockets. Armed with these primitive weapons, I managed to fend off these pesky animals in most situations. Being able to climb a tree was another skill that helped me to escape the dangers of being chased, trampled or bitten. However, the most menacing creatures were other humans.

One day I faced an older boy, I think I was seven or eight, and he was probably ten or eleven. For some bizarre reason, he picked on me every time he saw me walking along the road. He would then beat the crap out of me. I tried to hit him back, but he was faster and more muscular. I would throw stones at him, but he would do the same but with more force.

His family was impoverished, and his behaviour was possibly an outlet to relieve his anger or frustration that he might have faced at home. Or he was just merely an arsehole who didn't like me. After a couple of these incidents, I told my older cousin that I am facing these problems. My cousin took me to him. We went to a local shop in our village and then waited like hunters for the pray to come to us. When the bully showed up, my cousin beat the crap of him in front of me. I didn't want him to retort to violence, but I could not stop him.

For some time the bully left me alone. One day as I was walking obliviously along a road with my head deep in the clouds, a car suddenly stopped by, and the bully and another older boy jumped out. I think there was little time between them getting out and the first fist making to my face. Then they continued to hit the back of my head, my back and belly for a short time, but it felt like each passing second was an eternity. I fell on the ground. Fists turned into kicks. They left shortly after that. Being kicked in the crotch was probably the most memorable pain from that encounter. I can't remember if I pissed myself.

I felt blood in my mouth for the first time by being punched by someone other than my father; although my father's punches were on a different power-level and his fists were hard as bricks*. Thus the account with the bully wasn't particularly terrifying. I didn't say anything at home. I didn't say anything to my cousin, either. But luckily the bully left me alone. I think he found some other hobby or got bored because I didn't give him the satisfaction of showing any fear.

*I dropped a few of them on my feet when I was proudly helping to carry them when my grandparents were building our house.

I kept going to pick more books in my local library. I knew at the time that I need to get out of that place one day, and education was the most attractive possibility that I could think of. Individual's muscle power can leave bruises, but knowledge can either help us build, wipe entire cities, species, or intelligently woven mental schemas can sway the whole nations.

When I got older and more physically built, I still had an urge to go back, confront the person and remove a few of his teeth. The guy spent some years in prison after causing a severe road accident while under the influence of alcohol. Luckily that prevented me from facing him and getting into trouble. When he got out, fate had other plans for him. While he was doing some maintenance work, a hot water pipe burst and scalding water killed the bully. I admit that I didn't feel any sorrow for his misfortune. That sometimes bothered me, but now I just want to carry on with the rest of my own life.

I don't believe in karma or afterlife, but instead, I think that all personal choices and actions accumulate and mould our lives. My intimidator made a series of impulsive decisions. Some can lead to more behavioural mistakes, and others lead to irreversible consequences. Few would blame his lack of resources or environment for his behaviour; I believe the only means he lacked were: his imagination and accountability for his actions. But I often wonder if I can blame any living being for this lack of cognitive capacity.

I knew I had to study, but the school was just dull. So I couldn't focus much on learning the things they told me to remember. I didn't have a royal background, so no one was bothered to help me out and set me straight. I wasn't bright enough to help myself, either. My grades were average. I also didn't like the post-Soviet schema of teaching by intimidation or humiliation; it was making me study less not more (maybe that was the trick Soviets used for their satellite states?). To fill the void of me not knowing what to do, I tried distracting myself by going out, meeting girls and sampling regular life which sometimes was quite fun - at least to an immature mind. But I eventually concluded that this kind of life is not fit for me either. I wanted to do something inspiring and to use my noodle rather than trying to fit into the society that I didn't enjoy.

When I arrived in the UK, I realised how bad things were without a strong educational backbone. "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others," Orwell's message still echoes in my head when I think of the beginnings. We can live in accordance to someone's else script if we ignore or skip too much of wisdom from the literature, or when you are not sly or fail to speak the language of the people around us.

Education can act as one of the pillars supporting the platform of our wellbeing. Despite reading the necessary basics, for a long time, I lived in a cocoon of ignorance until I realised that we need to build several such pillars to support our mental comfort. I believe these include:

- continous practice of improvement of managing personal assets and time,

- hands-on skills to do our jobs so we can sell our time for food and other life's necessities,

- learning how to choose good nutrition and cooking it,

- basic psychology gained from interacting with other people,

- and experience how to work with others to achieve things that are beyond our skillsets and constraints.

For most of my twenties, I overcompensated for my lack of education and tortured myself to catch up with things I missed in my childhood. While at it, I kept punishing myself inside, and I was often dissatisfied with my progress. Eventually, I realised that I spend so many years in education that I forgot why I was even there in the first place. Instead of joining a rat race, I became a lab rat.

Educational system, like many systems established by humans, can make one sometimes too dependant on it. Sometimes to accept oneself, one needs to get exposed to the wilderness outside the organisation.

I realised that life outside academia, or at least PhD, is scarier but can provide one with more freedom. 'Don't sell you soul!' someone told me once during my studies. But I don't like that statement, because regardless of what kind of job you are doing you should work to increase you financial comfort because it can give you the power to make more choices in life or opportunities to invest. That person didn't have to worry about these things, I, on the other hand, walked on thin ice living and lived in crappy places, so the message didn't resonate with me.

I said in some posts before, making wealth a pivot of your life can make you extremely vulnerable when things swing up and down around it. Any fluctuation in your wealth can pull your mood by the nose. It is an awful state to live in. But, unwittingly, I pegged educational achievement to my sense of wellbeing in a similar way. Every time I was stuck or didn't perform well as I hoped, I was mortally unhappy. Making myself to suffer like that was just an insane way to grow old.

So what am I trying to get at here? Don't be afraid to get out of the train of formal education if it makes you unhappy or financially constrained. When you get fed up with it, start making your hands dirty by trying other things. Keep reading or patch holes in your knowledge by learning from other people if you can to understand more how to do things. Be conscious, however, that there are still plenty of individuals who will want to manipulate into their compliance or exploit you when you are most vulnerable. There is no way of preventing them from entering your life, but I believe you can wise up with a few attempts.

I still often confuse in my mind the terms of education with personal wisdom. But wisdom can benefit a lot from continuous jabs of formal and informal knowledge. Perhaps, traditional education can act as temporary nutrient-rich streams for learning; sometimes, these systems define relatively rigid obstacles that are not initially permeable to outliers like me. Wisdom, on the other hand, is perhaps something that we can build on top when we venture into unfamiliar territories. We can create maps inside our heads to navigate through more extensive networks of rivers, that join large reservoirs of common knowledge. The delicate interaction of education and the act of exploration itself forces us to architect a stronger foundation of our intellectual framework. That's why I find learning to be useful.

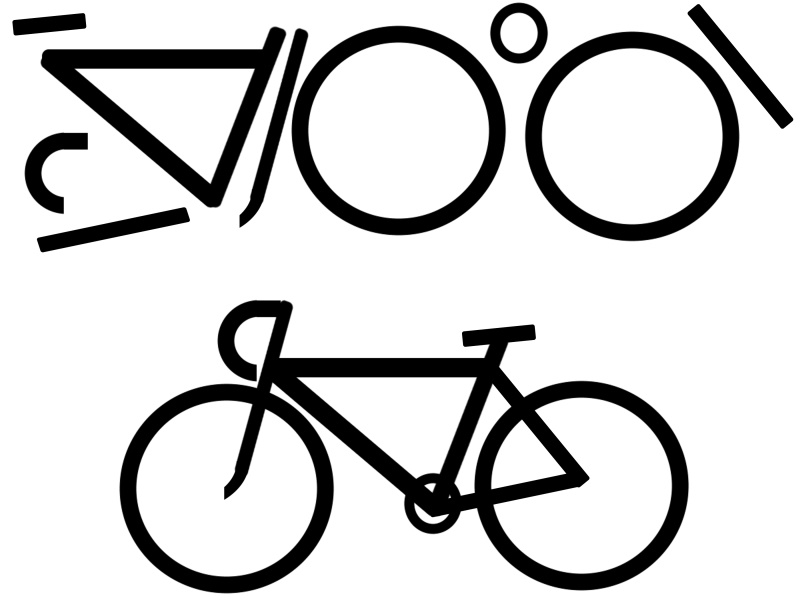

Perhaps it is easier to visualise education in the context of personal security using a gestalt principle that states: "the unified whole is different than the sum of its parts:"

When you gather some of the parts through education and assemble them in the right way through the experience, you can produce a construct, a bicycle in this case, that can help you get somewhere from point A to point B much quicker. That's why it can be important, and we must be careful not to dismiss its importance during our various livelihood pursuits. I hope I make some sense.

Vocational experience vs. theoretical knowledge* (* Please bear in mind this is my opinion)

If you want to be a plumber, a bricklayer, a baker, a paramedic, a nurse, a (f)irefighter (I think Police are ire-fighters), a radiologist, or a chef, I think you are making a great choice. If you want to be a physicist, an e-sports champion, an ethologist, a data modeller or a daytrader, these choices are also splendid. To find out what you want to do can be challenging for you. I think it boils down to running many personal experiments - trial and error sort to say - to discover what you find interesting and feel relatively good at. I think it is essential at the beginning not to strive for perfection* and ignore the inner and outer critics (* trying to be ideal, kills creativity in overcoming problems, too much brainstorming and no action can also be useless).

Bear in mind that some of us evolve and define our preferences faster than others, and even then these can dramatically change with time. We might even get bored with the things that we currently find interesting. So I suggest always to keep a few options open, if you are like me, or if you are often unsure which path is the right one.

When you work towards your profession, I kindly ask you to stop categorising people and placing them into buckets of worse or better jobs. One professor I met during my PhD had this tendency to look down at people doing manual tasks, for example, laboratory technicians. That was a fascinating discovery to me because, at the time, I believed that someone with more than twenty years of academic experience should be wise.

I realised that whatever we do, whether we have a great intellectual capacity, whenever one achieves a lot in life, those things do not make us immune to cognitive biases; in some odd cases, the biases get remarkably distorted. Watching people's reactions and behaviours, however, is fascinating because they can expose unspoken values these people record in their black boxes. The probed information can help us to influence* or predict the reactions of these individuals. Of course, if we want to play the game and learn to play our cards well. (* I don't tell you to manipulate them, I am just telling you to have an option too.)

"Until you stop judging people for what they do for work, you won't be free from judgment yourself," someone wise said. I keep that insight deep within my value framework. I also learned to accept that few understand this concept and that there is little we can do so stop them from making degrading remarks towards others. We can only stop short beyond simple influence.

I often had moments when I loved cooking and working in the kitchen. On some other occasions, I hated that work profusely. I didn't stay in the profession because the pay was not congruent with the costs of living and I doubted I see myself in career crafting food. Few chefs did well in the business and established well-running places of work. I didn't see myself in the industry doing hectic hours. Anyone can do this for a few years, but when we get older, our bodies can pay us back.

Sometimes the catering environment can be quite daunting and some clients can have unrealistic expectations (cough, *celebrities*, cough), but I have not worked a profession that didn't have challenges of its own. It can be a very thankful and fun profession, nonetheless. When everything goes smoothly, one can hear thanks at the end of the shift. Occasionally one can take home plenty of leftover food and a generous tip.

Vocational jobs can be very satisfying but incompetent individuals that perform their management duties poorly can suck out the joy out of whatever tasks we do. Some would argue that work is not about having a good time; I agree, but only partially. Work should be about establishing a trusting relationship between a worker and an employer. Both parties should respect each other boundaries and rights. Still, a competent employee (or at least trying to be intelligent) should grow to feel to be a trusted member who can take full responsibility for their actions. That way, they can develop into inter-dependence, that is, become confident in their skill and work with others to achieve organisational goals. An employer, in an ideal world, ought to supply the objectives.

Another point to consider is to begin learning the basic concepts of Minimax theory [4] and apply them to personal resources such as time and money. If you think to take a more academic path, consider how many years are you going to chase it for, and how much money are you going to burn in that pursuit. The housing bubble and poor renting market in the UK, for example, can mean that you might be worse off doing a degree for some professions. If you can, try to do something that you can study on the job. Be careful, of course, and consider a possibility that your employer/coworkers might not welcome your ambitions; in that case, keep it to yourself.

I think I spent too many years in education, but I, fortunately, realised early into my PhD that my scientific career is not going to take off. That became particularly apparent to me when one professor 🧐 uttered: 'So it seems that not all people that go Cambridge are smart.' Perhaps, I am not the smartest of the folks out there, I admit it, but I am also old enough to stop swinging my IQ 🍆 in front of other boys. I am not bothered anymore that my brain 🧠 isn't more buffed up; it is what it is. But what hurt me, at the time, was that I was bending over backwards to do my work, and that comment just made me feel that my effort is not appreciated.

Admittedly after drinking almost two bottles of wine after that event and throwing up over my wall, I agree with him ' I was not smart.'

Sometimes one can begin to grind their teeth like Stannis Baratheon, a character for G.R.R Martin novels when one hears one express a negative comment that your impostor syndrome gobbles up with rapacity. I decided to give it up as long as I defend my thesis, exit the chase and look for something new to do in life. I realised that childhood dreams are born inside an undeveloped brain, and now I was an adult waking up to reality.

At first, we can feel at a loss when we dive into an unknown. We may get overly stressed out, but eventually, we figure things out because we are very creative creatures. If you are approaching such crossroads, remember, you don't need to keep straight ahead. Still give yourself enough time to try your best, else make a turn to the side road and explore other views.

Some academics inspired me and left a lot of good memories, for which I will be eternally grateful. I especially thank Dr David Munday, Sir David John Cameron MacKay, Professor Malcolm Longair, Dr Peter Wothers, Dr James Keeler, Dr Philippe Blondel and Dr Matthew James Mason for being generous with their patience and kindness. I also bonded with a group of great people that, after so many years, I still occasionally meet up with. Some moments in academia can be timeless and leave a lifelong impression. The only way you can find out if that path is the right for you is to discover that for yourself.

Going to Oxbridge from a family of no educational history

I will be frank, I was not properly planning to go and study at a university level. It just happened. After dropping out of secondary school, I convinced myself, that intellectually, I have inferior intelligence. Sadly our common languages describe our shortcoming more frequently than we can find the words to praise ourselves*.

*quick Google search shows me 105 synonyms for 'stupid' and 35 for 'intelligent.'

No one in my immediate family pursued higher education, not because they weren't able; they didn't do it because they focused on different things in life. That was to some extend problematic for me because I wasn't sure whether I am making wise choices. On the other hand, I rarely heard anyone saying to me not to study STEM subjects. Besides, my grandmother always reminded me not to worry that much about my intellectual abilities. "We are born stupid and vulnerable, and we often, if we lucky, die being stupid and vulnerable, so you should try to remember to live in between these two points in time," she often claimed.

Many years flew by before I began to give myself credit. During this period I kept various self-defeating narratives looping in my head: "Maybe I am not good enough?", "I come from a non-academic background; perhaps I am not built to learn, explore and discover.", "What if others find out that I am some kind of fraud?" and so on. Slowly I shed the hardened exoskeleton of resentment that formed during my failed endeavour with early education. The crippled wings underneath it were too weak to take me through the metamorphosis into a fully functional adult. So I kept crawling on the ground and coped in the best way possible, avoiding others from stepping on me, until I could catch up from the all the majestic creatures proudly hovering on the sky.

When a dialogue inside my head appeared to change, I noticed a higher frequency of thoughts that defended me: "So why does it matter if I am not good enough." "Maybe I am not, why does it matter?" "Why do I have to prove to others that I am good enough at anything?" "Do I want to keep trying to fit bizarre standards or live to the whims of unrealistic expectations set by others?" "If I am not good, can I accept that?" "How much time do I want to set aside to get better?" "Is the time going to be well spent?" "The last thing I can do is to be patient and keep living my life and just accept the way I am."

In one particular moment, I exclaimed inside my head: "Eureka! My thinking has been wrong all this time! I only listened to a particular set of thoughts and discarded the others, more constructive ideas."

Finally, I realised that my thinking requires some chaperoning, and through the remainder of my educational journey, I began to change my internal dialogue. I backed away from having my self-worth exposed to the external world of judgment.

Very early in physics and engineering, we are taught that when we want to reduce any external influence in a particular system, we can isolate, or decouple, it by applying some kind of dampening, or separating, mechanism. So I tried to use these ideas to the way I am thinking. Cars, for example, have suspension systems that make them pleasurable to drive around - an effort for many generations of great engineering. So I thought why not to develop a better suspension mechanism for my mind so it can endure the bumpy ride on socially paved roads, that sometimes can indeed be bumpy.

I can't hide it, Cambridge education was intimidating. People were brilliant. Some were ultra-learners that could absorb knowledge at an alarming rate. But I didn't feel alienated there, and my overall experience was positive. I always felt welcome and mostly in charge of my development. The lecturers told us at the beginning that they won't be checking attendance, and it was up to us to make sure that we do the work. That arrangement was perfect for me. No one had to stand behind, breath on my neck and tell me what to do. At first, it felt like being in a state of free fall; I spent a significant amount of my time living in the library hoping that the weight of knowledge from the books can stop me from floating and feeling disoriented. In the library, I met a handful of strangers and friends that noticed that I need to get out more. I think that spending time with others and taking regular breaks helped me from obsessing about my learning.

Sometimes we hear in the news that Oxbridge are elitist institutions and it mostly suck in talent from affluent backgrounds. I am surprised that this surprises anyone. Affluent parents want the best for their genetic successors and will usually invest profoundly in making sure their progeny have the best resources to be outstanding. In Cambridge, I met individuals that were equally versed in arts, sciences and sports thanks to their excellent pre-university preparation. During one formal dinner, I spoke to a visiting professor from the United States. He told me about his short visiting experience at Eton College, where he interviewed teachers to measure their depth of scientific knowledge. I asked him what his conclusion was. At the time we had a few glasses of Bordeaux, he exclaimed with a burst of laughter: "they are bloody good!"

If I were to suggest to less affluent students who are considering making into Oxbridge, do your best, but try not to spend too much time ruminating about it, and I would recommend to minimise time of comparing yourself to others. The only comparison you should be making is to your future self, and ask yourself if you are passionate about your subjects. If you can't see yourself being better, then stop right there and come back to a drawing board and consider other options. Don't forget, there is life outside these organisations and if you decide to go and study in Oxbridge, focus on what you want to achieve rather than worrying too much on where you are. Oxbridge education record on your CV can help open the door to many opportunities, but it can also make overly anxious, if you let it. So be kind to yourself.

Polish and British education systems

Poland, as a country, was used and abused throughout history. I sympathise with my predecessors who fought for our freedom, in some ways, I am also annoyed with the lack of national cohesion and long term vision at certain historical turns that lead our country to vulnerability, and exposure to external cruelty. On many occasions, our national pride and stubbornness brought us to the knees. Today the population is still segmented internally.

I didn't have too much educational success on my turf. Sometimes that makes me upset because I miss walking alongside rural wild rivers with cattails and weeping willows growing on their sides, and smell of drying early-summer hay carried by warm puffs of air. But today I settled somewhere else, and I am trying to make the best out of it, even when I have to ignore an inner voice of Monsieur Faragé.

When I was growing up, I experienced an older generation of educators whose minds were cast by the mighty communist machine. The pedagogical approach motivated students by scalding them. Once a soviet hive mentality was hardcoded into our minds, it benefited those in power and tried to produce a fraction of the population that is self-doubting. Such individuals would be easier to control or bribed with vodka. Communists also helped to train neighbours to be "nice" to each other. If one stepped out of line, the "caring" neighbours were encouraged to report the offenders to the authorities. Then the offenders would be sent away by the state for long vacations packed with various gulag activities. The informants, as a reward, would sometimes get a boost on the property or social ladder.

Yet, few educators would slide valuable books under our noses that covered the rise of ideologies, including sly Christianity, the rise of Lutheranism, influence of Roman empire the spread of their intellectual architecture that influenced our cultures. The European history is so hard-baked in our current views and values that is something I always found intriguing. These were my early years of Polish education.

What I didn't enjoy was the lack of deeper analysis and the lack of challenge of that pre-adolescent developing logic. The curriculum mainly revolved around learning an endless list of facts. I believe it is important to memorise stuff, but sometimes it was just too robotic and felt like a mindless regurgitation of things written in books. I wanted to learn how to think. Yet, many of my peers did exceptionally well despite facing these obstacles, so perhaps it is my lack of adaptation to the style.

In contrast, the British education, that I experienced, fleshed out the detail of our cultural heritage and focused on pragmatism and skill set needed to develop into subjects of our innate interests. I enjoyed the emphasis on learning to cooperate. My workload wasn't too bad either, and I could keep doing odd jobs for some extra pocket money. With spare cash to buy or borrow books to learn about Descartes, rather than having to sit through compulsory lessons where some uninterested students would disrupt anyway.

Furthermore, I enjoyed British education because our teachers treated us like responsible beings that would become adults. I wasn't nagged by aggressive individuals when I was studying or reading books on the corridors of my college. Although I can say that some serious incidents did happen in the proximity. On the first weeks in my college, some young adults got into a fight, and one of them was killed [5]. I learnt to stay away from certain crowds and concentrated on my studies. The last time I remember I tried to break apart a fight, my jaw or nose got slightly dislocated. It makes me sad to see that we have such weakness to tame the beast that tries to come out from underneath our skin and go berserk, but I stopped trying to be a hero for people that make decisions solely with their limbic systems.

The experience of both worlds presented me with contrasting methods on how we pass information between generations. I am probably going to be subjective here, but I had so much more freedom in the UK, at least before my doctorate, and I would rather have my kids to learn in this country. I hope I can give them this choice in the future.

Popping Oxbridge bubble

Before I decided to do a PhD, I tried to secure a job in the private sector. I was not very successful. I went through more than a dozen interviews. Despite networking, trying to get better through self-studies and improving my confidence by mingling with others, I only received bitter rejections. It was 2008, and the world was going through a recession, some jobs were still around. I kept working as a chef. Sometimes I also worked as a waiter and ended up polishing thousands of wine glasses a day. Occasionally I felt dreadfully beaten by a thought that "I am Oxbridge educated Polish wine glass polisher serving the elite that encourages people like me to do STEM degrees." Still, I kept clinging to my hope.

I began trying to secure a PhD post; a postgraduate degree could be an entry point into academia, I thought. The money was in short supply in all departments. Yet, I went through the interview process and landed a post without any financial backing. Afterwards, we started to think about how to get grant money to support the studies.

I can't remember the exact details now, but at one stage, I found a position at the University of Bath. The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) provided all financial fuel. So naturally, I applied, and got the post and moved there.

The beginning was a little bit like a honeymoon, well I never had one but can imagine. I was unsure of what I was getting into. At first glance, things were going fine, but as I moved further along the path of time, I was getting more disenchanted. I won't go into any detail, but if you seek to find inner happiness doing STEM subjects, then I wish you luck. Nonetheless, I decided to stick to my degree to the end, then I sold most of my books*, and I never want to think about the subject again. And that was the end of my scientific experience.

* Okay I still kept some, Richard Feynman's short books like 'The meaning of it all' and 'The Theoretical Concepts in Physics' by Malcolm Longair. I really like what Prof. Longair wrote on p. 157: "[...] This is a good example of how professionals work. They do not actually remember all the mathematics they have come across, but they keep their eyes and ears open to everything they hear, no matter how remote it might seem from their immediate interests; then, someday, these bits of information end up being important. They may not remember them exactly, but they know where to find them. These remards apply aptly to our understanding of the whole of physics."

Today, I still wonder what madness made me go through with my pursuit to try to get into academia, but I clearly didn't forsee financial repercussions of my decision. I don't want to sound bitter, but some parking spaces in London are earning more without learning to read. Besides, if a block of asphalt can perform financially without making too much effort, I will find some way to do so as well.

Today, I am not hard on myself for my early educational shortcomings, because I realise that things are not that simple, and I often prefer a smiling technician that saves my day than an academic veteran that spoils my emotional ether with their ego.

Still, I would like to leave you with a thought that I often recite in my noodle: "When you believe that the people are around you are arrogant or ignorant, stop, think for a moment and ask yourself: am I, one of them?" I suggest asking yourself with this question periodically, especially when you think you don't need to.

Concluding remarks

This reality can sometimes bring a crushing realisation that even when you hold to your dreams by the skin of your teeth, it can still leave you uninformed, or put you in a cage that is slowly sinking into a bog of detritus of negative thinking. In my case, I decided to let go of my naive childhood pursuits and crawled out of the pit, brushed all the decaying thoughts that stuck to the robes of my mind, and headed in a new direction. My final message on the topic of achieving your educational ambitions: